How hemochromatosis affects your organs

Hemochromatosis (he-moe-kroe-muh-TOE-sis) causes your body to absorb too much iron from the food you eat. Excess iron is stored in your organs, especially your liver, heart and pancreas. Too much iron can lead to life-threatening conditions, such as liver disease, heart problems and diabetes.

There are a few types of hemochromatosis, but the most common type is caused by a gene change passed down through families. Only a few people who have the genes ever develop serious problems. Symptoms usually appear in midlife.

Treatment includes regularly removing blood from your body. Because much of the body's iron is contained in red blood cells, this treatment lowers iron levels.

Symptoms

Some people with hemochromatosis never have symptoms. Early symptoms often overlap with those of other common conditions.

Symptoms may include:

-

Joint pain.

-

Abdominal pain.

-

Fatigue.

-

Weakness.

-

Diabetes.

-

Loss of sex drive.

-

Impotence.

-

Heart failure.

-

Liver failure.

-

Bronze or gray skin color.

-

Memory fog.

When symptoms typically appear

The most common type of hemochromatosis is present at birth. But most people don't experience symptoms until later in life — usually after age 40 in men and after age 60 in women. Women are more likely to develop symptoms after menopause, when they no longer lose iron with menstruation and pregnancy.

When to see a doctor

See your health care provider if you experience any of the symptoms of hemochromatosis. If you have an immediate family member who has hemochromatosis, ask your provider about genetic testing. Genetic testing can check if you have the gene that increases your risk of hemochromatosis.

Gene mutations that cause hemochromatosis

A gene called HFE is most often the cause of hereditary hemochromatosis. You inherit one HFE gene from each of your parents. The HFE gene has two common mutations, C282Y and H63D. Genetic testing can reveal whether you have these changes in your HFE gene.

-

If you inherit two altered genes, you may develop hemochromatosis. You also can pass the altered gene on to your children. But not everyone who inherits two genes develops problems linked to the iron overload of hemochromatosis.

-

If you inherit one altered gene, you're unlikely to develop hemochromatosis. However, you are considered a carrier of the mutation [altered gene] and can pass the altered gene on to your children. But your children wouldn't develop the disease unless they also inherited another altered gene from the other parent

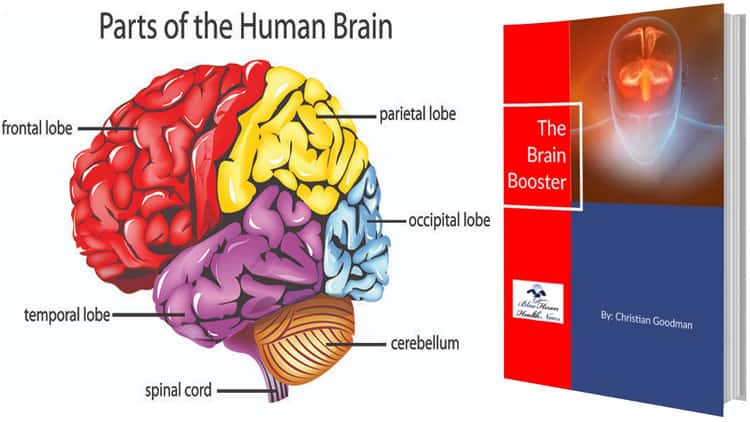

How hemochromatosis affects your organs

Iron plays an essential role in several body functions, including helping produce blood. But too much iron is toxic.

A hormone secreted by the liver, called hepcidin, controls how iron is used and absorbed in the body. It also controls how excess iron is stored in various organs. In hemochromatosis, the role of hepcidin is affected, causing the body to absorb more iron than it needs.

This excess iron is stored in major organs, especially the liver. Over a period of years, the stored iron can cause severe damage that may lead to organ failure. It also can lead to long-lasting diseases, such as cirrhosis, diabetes and heart failure. Many people have gene changes that cause hemochromatosis. However, not everyone develops iron overload to a degree that causes tissue and organ damage.

Hereditary hemochromatosis isn't the only type of hemochromatosis. Other types include:

-

Juvenile hemochromatosis. This causes the same problems in young people that hereditary hemochromatosis causes in adults. But iron buildup begins much earlier, and symptoms usually appear between the ages of 15 and 30. This disorder is caused by changes in the hemojuvelin or hepcidin genes.

-

Neonatal hemochromatosis. In this severe disorder, iron builds up rapidly in the liver of the developing baby in the womb. It is thought to be an autoimmune disease, in which the body attacks itself.

-

Secondary hemochromatosis.This form of the disease is not inherited and is often referred to as iron overload. People with certain types of anemia or liver disease may often need multiple blood transfusions. This can lead to excess iron buildup.